To the Ridge of the World, Tibet 2006

May 12 (Kathmandu)

|

|---|

| Same old Thamel, business as usual after riots |

Visiting Tibet was Cheng's dearest wish, and I decided to take this study vacation month to fulfill that. Was faced with quite a few turbulence initially. Firstly, we had hard times finding travel partners, many of them backed up reasonably due to other commitments. Travel fares were jacked up tremendously due to the group of three only. Secondly, due to the Everest route we were taking, we were making transit from Nepal to Lhasa. In previous month, there were frequent demonstrations and riots against the King, clashes with polices on many streets even in capital Kathmandu, leading to several deaths and injuries. That made us worrisome, so much so that we kept watching CNA for Nepal new updates. Fate once again tested our determination of stepping onto the land of Nepal, (just like the previous trip), even when we were just by-passing. Very fortunately, Lady Luck smiled upon us (and the Nepaleses) just 2-3 weeks prior to our departure. The Nepal king gave in to the people power and subsequently riots dwelled away; moreover, the Maoist army declared three months of ceasefire against the government. Hence, Cheng, Isaac and I sneaked such golden time to make an early flight via Thai airline to Kathmandu on this very day.

At the Kathmandu airport, we got ourself the free gratte visa (of up to three days) by handing over passport photo. We stayed at Hotel Vaishali in the tourist-concentrated Thamel district. Across the street lane from Hotel Vaishali was Hotel Nature which Cheng and I acquainted Saru in our 2003 Nepal trip. Saru, our dear Nepalese friend, was so eager to meet us again after two year of constantly emailing that she left her contact to Hotel Vaishali even before we checked-in. We arranged to meet her for dinner later on after making some shopping errands around Thamel. Being here the second time, we had no problem wriggling around the streets straddled alongside with touristic shops without any map. The roads, shared among cars, bikes and walkers, showed no signs of maintenance as they were gravelled with pot-holes accumulating water from the previous rain. We stayed alerted of any incoming vehicles and splashing water. We witnessed a rare wedding occasion as a decorated car squeezed through the narrow lane, led by a trumpet band blasting its way through and relatives dancing along. Every shop was operated as usual and people were back to their usual lifestyle. Thamel was soaked with rains but was not drenched by riots weeks before. It still retained its uniqueness which we experienced before; but our appreciation of its charm was lessened by familiarity. It was the same old Thamel as before without any traces of modernisation due to the recent country turmoil.

In the evening, Saru brought a surprise guest -- her young niece with chubby face and bright eyes to our rooftop dining table. Saru appeared more matured yet upheld still her friendliness which we adorned of. We exchanged our gifts of friendship and had a wonderful mango dessert kindly sponsored by Isaac. We agreed to meet up again once back at Nepal from our Tibet trip. This night we tried to get a good night sleep because we knew for sure that in the next few days of staying of oxygen-deprived highland, we would not have such luxury.

May 13 (Lhasa)

This morning, we boarded an Air China to Tibet. The flight seats were internally riddled of Chinese advertisements within passengers' line of sight. It was an hour journey across the Himalaya Range. Unfortunately, such mountaineous magnificence was curtained utterly by clouds. Nevertheless, Isaac felt the sheer blanket of cotton clouds captivating enough to experiment upon his Panasonic camera which he had struggled hard to purchase.

Gongkar airport was compact and cleaned. Bureaucratic regulation only allowed visitors to enter the so-called Tibetan Autonomous Region in nominal group. After showing a group-visa permit (which we had gotten to arrange in Kathmandu) to several custom officers and passing through scanner check, we were finally intercepted by our tour guide. His name is Phu. In his mid-30s, his single-lidded eyes hollowed within his poker face. He broke the ice by opening up conversation with some senseless jokes and his laughters made himself more approachable.

|

|---|

| Barkhor Square |

It was 92-km drive to Lhasa city. We bypassed the new QingZhang railway track and Qinghai-Tibet highway, which were access points for the influx of Chinese people to infiltrate into the Tibetan region. (By the time of this writing, the QingZhang railway route was officially opened with much international coverage, which spelled the new era of economic opportunities to the Chinese.) We even sped into a road tunnel cutting through the mountain, astonished by the high level of infrastructure in this land elevation of 3595m! However, such astonishment was paled in comparison with our shock of the city layout when we arrived at Lhasa western part. The road was cleaned and wide with many lanes, lined with oddly-shaped lamp posts. Slogans and shop advertisement were everywhere, mainly in big Chinese fonts of four or eight words. I thought I was in Beijing? Amid the city modernisation, I managed to glance several pilgrims taking year-long sacred journey by taking repetitive three steps and a bow miles from their villages.

We were relieved to stay at Hotel Shambala, right in the heart of Tibetan Barkhor Square. Barkhor area was the remaining part of Tibetan old town, surrounded by Chinese district of multi-story shopping centers and KTVs. Before we ventured outside, we had the discipline, in such crucial time of acclimatization, of forcing ourselves to sleep. Nobody had a good nap. Not only my heart was beating fast, pulses behind my head kept pounding against the pillow as the body was yearning for more oxygen and red blood cells. Even unpacking our luggage was at a slower pace. Once we felt much better without nausea, we took leisure stroll along the Mentsikhang Lam, one of the busiest lane of Barkhor Area. The place still retained the medieval-like white-brick buildings adjoining one another, occupied mainly by Chinese shops selling low-priced travel gears and shoes. Paupers, usually tattered woman shouldering baby and hand-holding another toddle were waiting on the street seeking for tourists' kindness for donation. Though as much as I wanted to give, I suppressed my sympathy to avoid promulgating begging. We entered into Tashi I restaurant which was highly recommended in Lonely Planet. Aside from the internal decorated with portraits of ghastly-looking Tibetan normad ladies, we were nevertheless pampered by popiah-like bobis and cheesecakes. Later, the post-dinner stroll brought us to the night stalls steamy with fried food as well as to outdoor pool tables crowded with locals. We did not walk much furthur to Barkhor Square as we left that for the next day.

May 14 (Lhasa)

|

|---|

| Jokhang temple |

Phu was waiting for us in early morning to take a short walk to Barkhor Square. It had been once a gathering place for riots, now it was bustled with poeple selling accessories, walking around clockwise the pilgrimage circuit along the Jokhang parameter while swirling portable prayer wheels. In front of Jokhang facade, the Tibetans were offering their prayers to accumulate merits. Even an old woman with pony-tailed white mashy hair, followed the ritual: palm closed while standing, before gradually lowered to lay flat onto thin worn-off mattress, then hands rested on wooden pieces to glide forwards to complete the posture of total humility, recorded the number of times she performed by shifting bead along the necklace string before eventually getting up with great effort to repeat the cycle again. I witnessed for the first time in flesh, the level of devotion to attain bodyless mindfulness. Chinese visitors wriggled among the devotees busy videoing the religious activities mindlessly. Phu even told one of them off for trying to invade into a prilgrim's tiny space without respects.

|

|---|

| Potala Palace Under Survelliance |

Ticket to Jokhang interior was a square compact disc (which I am still figuring out how to play it on my CD player). Phu corrected us, saying that though Jokhang was made famous by Princess Wencheng, Chinese wife of King Songtsen Gampo, it was constructed way before she arrived to Tibet from ChangAn. Our first exposure to hallmark of Tibetan Buddhism, was Jokhang inner sanctum. (Tibetan Buddhism, deeply ingrained in locals for centuries and the religion of actor Richard Gere, was a fusion of India Buddhism and Bon, the latter a shamanic folk religion workshipping ghosts and demons.) It was appropriate to walk clockwise along the short Nangkhor Kora (Pilgrimage circuit) to visit various small chapels with seated figures of Buddha and renounced Tibetan images. Phu, paying respect to his religion, hummed in Tibetan prayer words erratically. Some locals climbed up a small ladder to touch their forehead on the bronze Buddha's lap. I did likewise, praying that He would bless us in a safe journey onwards. At the roof of Jokhang, the golden spokes of Wheel of Kamaric Law made a striking comparison against the brillant blue cloudless sky. Roof view overlooked the whole of bustling Barkhor Square, on the right corner soared the Potala Palace, furthur which was the hill ranges white-capped by abrupt snowing the day before. (That explained total cloud obscuration against the Himalaya range when we flew.) The strong ulta-violent rays in Tibetan highland compelled us to buy cowboy hats to shade our faces, as well as posed like actors in 'Brokeback Mountain'.

After having lunch and a cup of horrible salty and sour yak butter tea, we proceeded to the Potala Palace, the once residence of the Dalai Lamas and now a huge soulless museum labelled as World Heritage Site. Snaking up the Potala was puffing. The White palace was a cluster of layered buildings with high windows. The Lhasa new city, converted from swampland into a network of flats and factories, was within our glances. The chapels within Potala was cooled by the conventional air and unique architecture; even the incense lamps, fueled by yak butter consistently replenished by lamas, flamed eternally. Some of quarters were closed for renovation, regretfully one was the bedroom of the current Dalai Lama. There were three floors, accessed by climbing those shaky wooden ladders. There were several quarters of Dalai Lamas of many generations and converted into chapel once they went for another reincarnations. Their ashes were stored in the chortens (stupas) at the Chapel of the Dalia Lamas' Tombs. The most magnificence of all was the gigantic 14 m tall chorten of the fifth Dalai Lamai, tainted with 3700 kg of gold! To ensure that Potala bred no dissidents, there were more wired surveillance cameras, almost in every room, than those in Jokhang.

We found Potala Palace best admired from outside than inside. Its landscape dominated the Lhasa city, like a red and white giant, sitting upon a small ridge yet cupped within the surrounding mountain range. In front of Potala entrance was Tibetan village no longer, but was replaced by gift shops and spacious square, mimicking the Beijing Tiananmen Square. The Potala scene would be something we remember for life.

Before dusk, we made a trip back to Barkhor Square and encircled the famous Kora (pilgrimage circuit) around Jokhang Square. Following the Tibetan culture, I got myself a small prayer wheel to swirl while strolling. The circuit was littered with stalls of religious iconic souvenirs. Isaac managed to captured a shot of a chubby toddler with his hind pant opened with a hole for his anal release. Everytime he looked at the picture, he was amused. A young man shouted right in front of my ear asking me to look into his fake Tibetan Heaven's Eye jewellery and made swearing remark when I simply walked away. I was puzzled by his threatening service and could have turned back and scoffed at him harshly. But to amplify my anger near such holy temple was nothing but incongruent, not to mention accumulation of bad kama, although I could not speak likewise of him. We had dinner again at Tashi I to enjoy the delicious cheesecake, yet we found the dessert was not as tasty as before. Our memories often brought all good things into boredom, perhaps that why societies were forced to improve or get eliminated.

May 15 (Lhasa)

|

|---|

| Drepung Monastery |

This day we paid visits to monasteries at the outskirt of Lhasa. We were introduced to Yang, a sturdy-built quiet adult in his 40s as our driver for the rest of our trip. He drove us some 8 km to arrive at Drepung Monastery, one of the largest monasteries populated by thousands of lamas. Phu, led us up around the towering white monastery buildings. Golden prayer wheels were located intermittently along the perimeter allowing devotees to turn clockwise while following the kora circuit. Mani stones were craved in Tibetan sutra spelled Buddhist blessing. Way up above the mountain slope stood boulders painted of Tsongkhapa and his proud discipline, encircled by prayer flags. Drepung Monastery was bundled of three-floored buildings leaned onto the slope like a stairway. Each whitewashed building was mainly pocketed with black-framed windows, with sills of flower pots and lintels fluttering with white curtain lining. The opposite distant view was endless mountain range floured with recent snow.

|

|---|

| Diligent Lamas at Sera Monastery |

Beside the grand overview, we also discovered intriguing things of smaller scale, such as concave disc reflecting strong sunray to boil kettle perched on top, an ancient hand-drawn Tibetan currency note, and big chuck of flesh yak butter wrapped on animal hide (which we had a good fingertip taste of it in a mass kitchen). Phu recommended Cheng and I to buy souvenirs at this place as the profit goes direct to the monastery, holding no motive of seeking commission elsewhere. Every indoor quarter required a small token before photography was allowed. The only place we paid out to take shots was a spectacular hall of array of red pillars and hanging victory banners, assembling hundred of studying lamas. Every lama was lap-sitting in rows on thick red mattress, slouched inside his red robe, swaying continually while reading out from unbounded rectangle pages of wordy scriptures. During their recess, they loitered around the road and mingled around within themselves like school children. Before we departed from the fine lama college with an air of serenity, a teen lama who was on duty to fetch well water sent us off with his greeting and innocent smile.

|

|---|

| Lama Debating at Sera Monastery |

We were back to Barkhor square to have lunch at Tibet Lhasa Kitchen which served mouth-watering roasted chicken and cheese soup. (Pardoned to this place which advocated the transcendence away from sensual yearns.) Such sumptuous meal did not pay off during the afternoon trip of Sera Monastery as we all felt slight stomach squeamishness. The oxygen-scared Tibet highland caused our bodies to slow down and lead to indigestion. Sera was one of the two Gelugpa monasteries besides Drepung. Many Tibetan parents brought their toddles in front of the statue of Tamdrin, a 'horse-headed' wrathful deity, and the blessed children came out with smeared black ink in between their eyes. In the north east corner was the debating courtyard where initially all the lamas were sitting together in one big red patch, executing ritual for a newly erected prayer pole. They were chanting in harmony although some stole time for a little chit-chat. A lot of foreign tourists were surrounding them, much-anticipating the next activity. At around 3-4pm, the lamas conducted their debating routine. Such unique debating involves one lama standing to pose questions at one or many lamas sitting helplessly on bare grounds while the questioner often pointing ferociously and clapping his hand loudly to emphasis his point . The questioner might laugh away or tap gently on the answerer's shoulder or face to ease the tension. Even a lama kid could pose questions to their seniors. Through such seemingly heated argument, they were actually having Q&A session about the Buddhist perspective of the universal. Besides the foreigners busy snapping their cameras away, there were a couple of old folks who came all the way from Bhutan, to witness such extraordinary religious culture. Amid their debating, a few police guards were walking around, ensuring orders and no anti-society talks.

We returned to Tibet Lhasa Kitchen again in the evening to taste its fried spring rolls. Because this was the last night of Lhasa stay, Isaac made his last-minute shopping to get a very good bargain for a full suit of warm outfit from an amicably kind auntie. I appreciated very much that Isaac lent me his other warm clothing, as I had overestimated my endurance towards coldness by bringing only few dress pieces. Guessed it has been quite a while since I been to cold highland.

May 16 (Yamdrok, Gyantse)

We packed our bags into Yang's black four-wheeled jeep to explore what Tibet truly was outside Lhasa. At the start of the ignited engine, Yang moved his vehicle sluggishly while mumbling in prayer call much like what Phu did in any monasteries. He prayed for safe journey. Whether his call was heard of, the whole drive throughout the trip nevertheless ran smoothly with no hiccups. After Isaac exchanged money in Bank of China and we loaded a carton of mineral waters, we drove along the Friendship Highway, a 920 km road length between Kathmandu and Lhasa. The road was flat, wide and well paved initially, yet Yang had to skillfully and gradually overtake many goods-transporting trucks and lorries. Soon, we deviated from the highway and travelled southward towards the Yamdrok Lake. The route was now a steep wriggling ascent around contours, well maintained and railed regularly by road blocks. I monitored closely at the altimeter attached to the car front, knowing that we were gaining by 1000m height swiftly. The hilly brown slope was tainted by patches of melting snows, akin to chocolate ice-cream.

|

|---|

| Yamdrok Lake |

Finally in a single bend, the Yamdrok Lake suddenly revealed itself and we stared, mouths widely opened, in awe. Yamdrok Lake was coiled around the bonders of snow-flaked mountain, in still blue within any ripples. We now stood at Kampala Pass of 4794 m high which sent the first sight of this holy lake. It was littered with touts, constantly urging us to take pictures with their decorated yaks and dogs. We gave in to a mercenary yak owner, only to charge us more later for shooting him into pictures. The tout interruption was really spoilsport; and Yang brought us downhill to a secluded cliff edge to have a better appreciation to this sacred place. Such large azimuthal lakeview was heavenly and we spent minutes overwhelming ourselves. As we descended furthur, skirting around the lake level, the dazzling water reflection of mountain range was more pronounced. Normadic sheeps were grazing on the grassland by the lake. Once again, we requested for a picture-taking stop and eventually we hit our camera memory space limit.

We had our lunch at Nangartse, while doing some photo file management on my portable hard disk. The restaurant provided low-levelled table, which we had to bend down to sip up plain noodles. We moved westward towards Gyantse. The dirt road onwards was bumpy inside mountain valley. Everywhere looked brownish and harsh, and the shepherds were chasing the sheeps into greener pastures. To keep away road dirts aroused by incoming trucks and yet allow interior air circulation, Isaac had to wind up and down the car windows in check of incoming traffic. Mountain peaks were constantly within our outlook. At one of the mountains peaked 5600 m high, it soared in board shoulder and marshed with thick snow piles. Despite such hostile, freezing, brown environment, there were normadic people gathered beside their pitched tents, tiny guesthouse and open toilet(only half-raised by rocks heap with admission of RMB 1). At Karola pass of 5010 m high, we took only a brief stop to admire the barren upland before the extreme cold and strong wind compelled us to take refugee in the vehicle again. By this time, my numb hands and my tumbling head threatened me to admit my foolishness of not wearing thick...

This 7-hour journey ended in Gyantse, 254km south-west of Lhasa. We were fortunate to stay in the luxurious Hotel Gyantse (needless to say it was government owned), and were impressed with the golden-ornate reception as well as the allocated large room with colourful Tibetan design with complimentary Longjing tea. Before nightfall, we appeared in the street seeking for food. It rowed out with Chinese shophouses and eatery, lesser of city vibrancy with no beggars in sight. Dinner was consumed at Tashi restaurant. The restaurant owner's furry puppy amused the patrons with its cute presence, although it was not impressed with Isaac's chocolate bar. After meal, our tour at Gyantse street was short-lived in merely small walk at the wet market, because not only it was small and straightforward, but also I was still suffering from the after-effect of the cold . Notwithstanding pulses behind my head constantly pounding, I still managed to sleep soundly due to the hotel room coziness and much hot water.

May 17 (Gyantse, Xigatse)

The buffet breakfast was served in a large hall topped with Chinese phoenix and dragon and walled of scenery paintings. As much as the meal was very conducive for early appetite, I ate it without full conscience to enjoy such high luxury. Our first and only stop in Gyantse was at Pelkor Chode Monastery compounded with Kumbum. Pelkor Chode was currently the remains from a complex of monasteries after Chinese Revolution, still much to browse around. It retained shelves of coffin-like boxes of ancient sutra manuscripts as well as lifelike figures, ranging from unmoving Buddha, body-twisting Bodhisattvas to wrath-looking deities. The interiors, networked with electric light bulbs, was no longer creepy dark as before and visitors no longer required torches. We observed a lone lama cuddled at one corner of the chapel, mindful over his vocal chanting and occasional bell-ringing. Slight incense smoke permeated the rooms to appease all hurrying visitors. My heart was at peace with the monastery, and all the petty social lifestyle I had always been trapping, were not relevant here.

|

|---|

| Pelkor Chode Monastery (right) and Kumbum Chorten (left) |

Next to the Pelkor Chode Monastery was the Gyantse Kumbum, an oversized four-story Chorten of 35 m high, packed with thousands of Tibetan paintings and sculpture wordings. Loitering around the first few chapels gave us an idea of what the rest would offer, so we skipped the rest of the tapering floors and headed straight to the roof top. After a ascent panting hard for oxygen, the roof top rewarded us with an overlook of Gyantse households spiked with prayer flags and Gyantse Dzong, now an anti-british imperialist museum topped on a small brown knoll. A fat golden tower rested on four set of Buddha eyes gazing directionally, with four hard chains pivoting the dome. During our last-minute photo-taking down from the Chorten, Cheng acquainted a young Tibetan boy with nice outfit and Chaplin's cap. Speaking in different language, he chose to mute and expressed his mischief and affability together by playing with her hat and hugging behind her strongly.

Along the route to Xigatse, we stopped by visiting Pharla Manor, the outskirt of Gyantse. It was once owned by a noble family in Tibet kingdom who also enjoyed numerous land hectares, livestocks and servants. It had changed into a secluded museum managed by few gate-keepers and a popular place for film-shooting. The two-levelled main manor comprised of guest rooms carpeted with animal hides, mistress bedroom dotted with imported Shanghai cosmectics, warehouse showcasing exquisite collections and hunting revolvers, and even a severed head of a notorious criminal. There was a separate quarter for manor servants. Each room was vacant with handicraft tools left intact, photograph of resident was hung with paragraphs telling how he or she was liberated from slavery under communism and lived happily thereafter. Ironically, this place signified past glory of Tibetan Kingdom, was listed as the current base of educational demonstration and national patriotism in Tibet Autonomous Region. This was no wonder that we watched several Chinese officers driving their patrol cars to visit and comment.

|

|---|

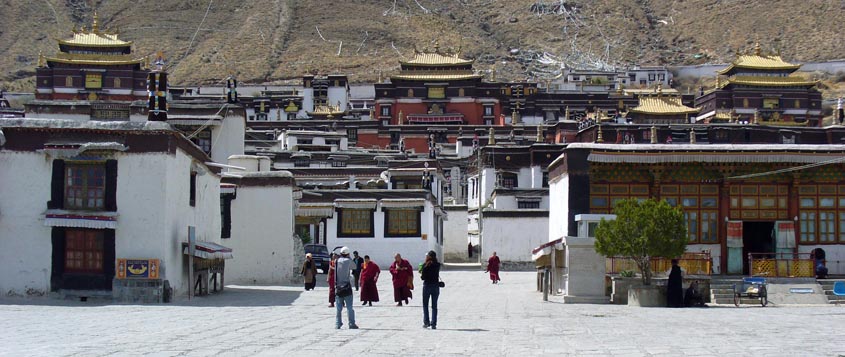

| Tashilhunpo Monastery |

In mid-afternoon, reaching Xigatse (3900 m high) was only an hour drive away. We had a quick lunch near the Hotel Manasarovar where we checked in, before proceeding to Tashihunpo Monastery. The monastery was the establishment of the lineage of Panchen Lamas, second only to Dalai Lamas in the rivalry of religion leadership. The present 11th Panchen Lama, probably the world's youngest political prisoner, was not even a step closer to this place where he could pearch and lead and his current being remained a mystery to this day of writing. Situated in front of a hill, it was congested with staggering mix of buildings in white and orchre. Up the cobbled lanes and once stepped on the chapel of Jampa, my jaw was unhinged and I exclaimed with an inappropriate wow. The entire room made way for one of the world's largest bronze statues of Maitriya (Jampa), the future Buddha. Made in 1914, the serene-looking, eye half-shut Buddha statue loomed as high as 26 m coated with more than 300 kg of gold, leaving the visitors speechless. Furthur up and passing through a stoned tunnel was the majastic assembly hall crowned in exquisite golds and of black-framed windows fluttering with curtain linings. It surrounded the cobbled courtyard of walls painted in rows of thousand Buddhas. I stood on the second level taking pictures of a local family resting down at the courtyard, an old lady saw my presence upstair, bowed her head and palms pressed. I treated that as a blessing as I smiled and did likewise with equal courtesy. At the side was a tall white wall where large thangkas would be hanging during festival. We did not come at the right time to witness such ceremony but was thus spared from crowd congestion. Phu told us secretly that this was a place where he was imprisoned for two months when he came from Dhamasala in India without a proper passport. His wife who also sought refuge like him in India and learned English together, bore him a son. Now despite all the small grudges, he seemed to be happy with his family of three. I prayed his well-being; although he was heavily addicted to smoking under social pressure, he was nevertheless a good man who sought solutions in a peaceful, forgiving way, much in a Buddhist way.

Yang dropped us at Tibean market, one corner of Xigatse. The market was just a 'pasar malam' selling small prayer wheels, religious icons and skinned goat meats. Those items interested us no more than just a brief walk before we headed to the street searching for dinner site. We had a hard time to find eating places recommended by Lonely Planet, only to spot a Chinese restaurant 'Greasy Joe's' in small English label. The food for trio turned out great at only RMB 35! A cab ride fared at RMB 5 spared us the trouble of walking long distance in the imminent sand wind. In the usual hotel nightstay, we often resorted to television watching to wait for bathing turn before sleep. There were many Chinese programs telecasted from various China provinces, but their advertisements were too long to entice me to follow through excitement of drama serial. (I remembered one nagging TVAd selling device which made several uncles appeared stupid by putting the metallic device round their shoulders and head for neck straightening.) Only Isaac would keep on watching and waked up the next morning with his black-socketted eyes.

May 18 (Rongbuk Monastery)

Major road construction furthur down the Friendship Highway forced us to take one big northern detour. Due to time constraint in taking extra mileage, we had to forgo visiting Xegar planned in our itinerary, and head straight to the Rongbuk Monastery instead. This day was spent most of the time sitting with our butts on the vehicle seats. Once we detoured away from the highway, the journey begun to be bumpy. We owned our safety to Yang who, having driven all over Tibet for 20 years, vigilantly overtook convoys of huge long lorries in narrow pathway. The mountainous terrain was more barren and much lifeless except scattered villagers, and nomadic sheep overcrowding the route. The wide riverbed, visited only by few migratory birds, was dried up.

In mid-afternoon, we finally returned to the Friendship Highway, skirted away from its roadblock. Our simple but satisfying lunch was settled in Lhatse (4050 m) town so simple that we did not even bother to roam around. Instead we hastened southward, gaining more and more elevation until we reached to the highest point thus far. It was of 5200 m altitude, all in a single day without sweating! A signboard, in Chinese welcoming words, was mostly covered up by countless prayer flags strung up and spreading radically down across the bare ground. The massive prayer flags in various colours, wavered hard in strong current, trying to bring their written sutra as high as possible to the heavenly sky. We got out temporarily without susceptible to altitude nausea. All our exciting remarks over this place were muffled by howling wind. From here, we descent slightly down while the dark clouds kept looming above us. At intermittent parts of the highway, construction workers were still laboriously repairing road or making drainage in thin air. Suddenly, apart from the window panes, I could not distinguish whether snowflakes or hailstones were falling down the brown soils. However once we turned into the new town of Tingri, it was sunny again. It was here where a British old couple met us again (lunch at Lhatse was our first acquaintance) in the same objective of getting mountain permits. They told us they had been to the freezing Moscow and were travelling to tropical Thailand soon. How Cheng and I wished that we could do admirably like them at their age, even though we were not born in a welfare state. At the entry of Chay village (4300-m), we had our permits checked and issued a environment thrash bag. It was an hour of road-wriggling up the slope, gaining height tremendously over the layering view of infinite mountain ranges. Eventually we reached Pangla Pass of 5120-m altitude, exposing a distant view of the Himalayan range like a marvelous white lining over the vast horizon. It was encompassed by mountains of over 8000-m, including Mt Everest (also known as Mt Chomolungma). A over-dressed yak, meant for photo-taking, was standing quietly right beside a stone table upon which yak skulls were rested. The wind was blowing ferociously, the young touts were persistently pestering us, but these did not deter us the ecstasy of reaching thus far.

|

|---|

| Mt Everest at the backdrop of Rongbuk Monastery (left) |

Later, we descent down again, across the barren plain and bypassing several rural communities. To our surprise, we came to a halt at a village and were told to unload our baggage. According to new environmental policy, all visitors were requested to transfer by a compact van driven by cleaner fuel at a fee. (Yet we saw few exceptions of self-driven jeeps making the rest of the trip to Rongbuk.) Riding via that small-wheeled van packed with other passengers and their belongings was utterly awful, all in the name of supposing green control. After a one-hour discomfort, we landed ourselves at the grand valley cornered the Rongbuk monastery in full relief. Rongbuk, at 4980 m high, was undeniably the world's highest monastery. Its architecture appeared plain and simple, however it provided stunning Everest view (which was currently overshadowed by cloud) and its lamas had been enduring sheer hardship at high altitude to gain enlightenment. See my sketch of Rongbuk Monastery. We were even more pleased to find out that Phu had accommodated us in a newly-built Hotel Chomolungma. The hotel was impressively located at such harsh plateau to provide high level of luxury by offering decent rooms of thick-mattressed beds and a restaurant. The neighbouring Monastery Guesthouse, which provided nothing more than basic flatbed, and shattering windows, was paled in comparison. Even though the forceful influx of modernization into Tibet was initially to be frowned upon, it was as such that my discomfort level in Rongbuk stay was kept minimal. Perhaps being a city dweller since young, I should not have the privilege to judge whether modernization is deemed fit for the Tibetan culture in a bigger perspective.

After a noodle meal at the restaurant upstairs where several locals and tour guides gathered around the steaming stoves, we turned into our individual rooms soon. Our sleep were challenged not just by the thin air, freezing temperature, but also wind trembling noisily against the double-paned window. Every time I was in transcend state and slowed my breathing, my body did not get enough oxygen and woke me to breathe hard. The truce between the sleeping monster and uneasy night stood past midnight. During such unbearable night, Cheng and I had to occupy ourselves by chatting, viewing our digital camera, and counting money notes. Soon, sleep deprivation overwhelmed me thankfully and I managed to sleep for a few hours. Cheng and Isaac were not that fortunate as they had to sit through the whole night staring at four walls.

May 19 (Everest Base Camp)

|

|---|

| Top of the World - Mt Everest (8848m) |

I was woken up by Cheng as early as seven, persuading me to peak through the snow-frosted window at the staggering view of Mt Everest, shortly before it was eluded by cloud again. The brown earth outside was flaked with snows, that explained the extreme chill caused by the blizzard the night before. At the breakfast table, Isaac's face was hollow in weary after withstood through the sleepless night. But as soon as Mt Everest exposed itself as the morning sun rose, he was animated again and could not wait to go outside and take numerous shots. We were so relieved that Mother Nature was generous enough to reveal the naked mountain the whole morning, else it would be another undesirable and terrible night stay again in the hope of seeing it the next day.

The option to go nearer the mountain at Everest Base Camp five km from Rongbuk was either to hike for hours or hitch a pony ride at RMB 60 per person. We chose the latter to avoid AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness) and spare our leg muscles. Yet the ride was far from comfort. Since the cart was pretty much improvised, the only dampening effect per passenger was a thin piece of mattress against the rocky trail. I was nearly thrown out from the hard seat if I had not hold on tightly on the wooden body frame fastened by nails; and my painful butt kept telling me to end the journey. The ride by Isaac and Phu was even worse as their uncooperative horse moved like tortoise and they were left far behind Cheng and I. Having said that, I was still appreciative by such excursion as my awe inched as I got closer to Mt Everest, looming larger and more majestically.

At a running stream across the vast plain scattered by yaks busy gazing on grass food transported by themselves, together with other equipment for the expedition team, we finally stopped at the Everest Base Camp at the elevation of 5200 m. A row of tea tents and guesthouses, seasonally set up by Tibetan communities, aligned along the route axis, welcoming all expedition teams and sightseeing visitors. Cheng was eager to retreat into one of camps, as she no longer endured the pounding frost air. In her first time, she was experienced numbing on all four limbs despite heavy thermal wear. On the verge of breakdown, I consoled her by pasting two heat pads on her legs. Tibetan hosts were kind enough to heat up the room by burning dried fouless yak dungs and offered hot tea to us. Eventually Isaac and Phu joined us to encircle the steaming stove for warmth together. When Cheng was feeling much better, I chased after the zestful Isaac who had already walked far away from the tent cluster, shooting paranomic pictures relentlessly. We were staring at the imposing north face of Mt Everest, right down below was brightly dotted with tents pitched by summit-conquesting team. Mt Everest was literally the highest point of the entire globe - 8848m. In Tibetan name, it was named as Mt Chomolangm, 'Goddess Mother of the Universe', being so respectable and sacred that Rongbuk monastery was built in adjacent. We pampered ourselves with body-warming chocolate biscuits in this once-in-a-lifetime experience. There was nothing more I demanded when Mt Everest was right in front of my eyes simply travelling by wheels without perspiring. (In Nepal, I would have to hike laboriously for miles just to see the other face of Mt Everest.) Cheng was feeling much better in heated enclosure by the time Isaac and I returned. Isaac photographed at those nomadic Tibetans with rosy cheeks and over-tanned skins, and they played mischievously at his funny red-haired cap.

It was then all the way back to Rongbuk, of more down slopes for the ponies to gallop faster and shock our butts harder. After a prolonged hind pain, we headed back to our hotel and prepared for departure. Once again, we had to be traversed on the environmental van, inside which we met a young punk with cowboy outfit. He initially chatted amicably about how he bribed his way through travelling alone in Tibet. Then it came to my annoyance when he showed off his national chauvinism, shamelessly boasting about his hometown's tall mountains right in the place no furthur from Himalayan range! Rebuking him I did not, I just did not offer him a seat to our jeep and seeing him stranded alone asking around for a hitch ride was my little wicked punishment to his arrogance.

Yang intercepted and brought us to a nearby village for lunch. The eating tavern surrounded the carpeted benches in low tables. A government-endorsed certificate was hung beside the wallpaper of Premier Mao at a corner, nearly covered up by shelves. We proceeded furthur north along unclear route to Tingri. In the hours of driving, the scenery skimming through was undoubtedly out-of-the-world. Green grass plain was littered with grazing sheeps and yaks, resting adult shepherds as well as curious children running to wave at us. It occupied the high plateau in sheer vastness and diminished the distant overlaying mountains. Regretfully, we did not ask Yang to make any pit stop to indulge more in the scenic moments as the overnight percussion completely exhausted us out. Had we arrived in steep climb from Zhangma through Nepal border via jeep directly, we would have taken our time jovial over what was around us, at the much higher risk of getting AMS. As a result, we reached our next accommodation early at the old Tingri (4390 m high) . It was plain town, commonly as a transit to Everest Base Camp with no fanciful hotel, hence Phu got us the best guesthouse named An Duo. Nevertheless, it was a simple guesthouse with no more than twenty padlocked rooms and welcomed us with washing basin filled up from a well. The common toilet was simple - two holes for different genders barred by a wall. Despite lack of amenities, the waitresses, who even dressed in pink uniforms, treated us well during dinner by habitually pouring tea whenever our cups were not filled to the brims. Throughout the trip, all of us were impressed with Tibetan people who maintained good hospitality services, at all places without a frown (even without going through Singapore's 'Go the Extra Mile for Service' Movement.). It might be their inert culture and mindset to help and please others. Before the sky sparkled with twilight stars, each of us knocked out on hard and flat bed which guaranteed lousy sleep, causing me a shoulder ache the next day.

May 20 (Nylam, Zhangmu)

|

|---|

| Nylam |

This day was a road trip south to Nepal border. We stopped not far from Tingri to take the last glimpse of blue-hued Mt Everest distant away from the brown plain. After bidding farewell to the highest peak, we were having an short ascent to Tongla Pass (5002 m). Naturally we halted at the pass shortly to cherish the divine instant immersing in the sea of cloud. Yang silently prayed at a ground filled with volumes of prayer flag strings and tied his kathak (a white Tibetan prayer scarf) among one of those flying. It was not hard to observed that every single Tibetan, whether city dwellers or rural villagers, young or old, sharing the same devotion without dispute. Their interesting cultures were ingrained deeply and withstood strongly against oppression.

From then on, we were losing height increasingly, through barren valley browned within snow mountains to a more-opened grass plains pocketed with acres of farmlands. By mid-afternoon, Nylam at an elevation of 3750 m only was within sight. It was merely a one-way town alongside with several Chinese grocery shops, guest houses cum restaurants, where a sharp snow pinnacle was loofed behind. We had a lavish lunch as our appetites gained back at lower altitude. Instead of staying here tolerating a mountain-breezing night, Phu decided to bring us all the way down to Zhangmu instead where it was warmer.

Journey towards Zhangmu surprised us with many viewing spots of cascading rivers, minor waterfalls and white mountains, now more distant in the alpine zone. First, there was this 5-m tall ice boulder spilled to the road as a result of avalanche and it was literally sliced through to create passage for vehicle. We posed comically around this gigantic block and threw ice scrapes at each other. Then we winded down the steep hill contours into the temperate zone lush with greenery. At a pit stop where below our foot was the road snaked all the way down to our direction, Isaac was pretty much engrossed in snapping at the blossoming spring flowers. At a point where the route passed under a small waterfall, our jeep halted a while as the descending water washed away the sands gathering from the past voyage, marking the end of our trip at the highland plateau. The thicker and fresher air dispelled our regular headaches. When we passed through a narrow lane squeezing our way through convoys of Nepali Tata trucks parked alongside, we had reached Zhangmu. Moving in snail speed, several ladies seized the opportunity to tout us into exchanging Nepali money with their handbags full of money notes. Zhangmu, was a border town between Nepal and Tibet belonging to the side of Chinese custom, situated on the hilly slope of only 2300 m elevation. Being the trading stopover for both countries, it had a confusing population mix of Han, Tibetan and Nepali. We lodged at Zhangmu Hotel, which reception was at first floor. Even though it was graded as top end, it seemed like we were the only occupants staying in a dorm room of ceiling with water marks and window view of hazy forest. The common toilet at a haunted basement provided no bathing facilities; thus three of us, not having been washing up even since the Everest journey, were willing to pay fee to shower at the opposite Gang Gyen Hotel. After a refreshing body-cleansing, we pampered ourselves for a steak dinner at a restaurant in European coziness, served by Nepali waiters and a Han lady boss who slinged her purse at all time. In the last night of our Tibet stay, Phu joined us for the meal and intrigued us of his stories in his years of tour guiding, especially his journey to unchartered Changtang Nature Reserve, north-western of Tibet dwelled by the hitherto mythical Yetis (Big Foot).

May 21 (Kathmandu)

The Chinese custom office was only adjacent to our hotel. However, before it opened in early morning, we were already lagged behind in a queue lined up by a Japanese expedition team, probably conquered some mountain as evident from the excessive skin-burnt members and burdens of ski poles, and several Western groups having difficulty understanding the custom writing procedures. Several trucks started to move out, horned continually asking the easily agitated old US couple to make way. During one hour of queuing, we were amused by a commotion which a young official in his parading soldier outfit, shooed off and argued at a Nepali gangster-looking worker who tried sneaking through without passport in hand. By Phu's assistance through his acquaintances to custom officials, we finally went through the custom. It was only a short hasty ride to Friendship Bridge where we bid farewell with Phu and Yang and rewarded their guide monetarily. We were intercepted by the representatives from Nepal agency with whom we followed to walk past the bridge where a line were drawn to distinguish between Tibet and Nepal. It was only a simple arrangement to clear the Nepal custom before we loaded up into another jeep heading back to Kathmandu. Not far from the Nepal border with a series of ramshackle houses along the pot-holed road, our path was blocked by a landslide due to the last night downpour. We stayed patiently inside another jeep, already immune to any waiting hour. Fortunate enough in a four-wheel drive, our jeep maneuvered through the massive mud and rocks, leaving behind the traffic jammed with big tourist buses and transporting trucks.

The rest of journey was much smoother, except a few military road blocks due to the recent Maoist insurgency. The tar road, due to its strategic trading pathway, was nicely paved through terraced farms, running rivers and ample forest greenery. As the AMS syndromes disappeared, our senses of humour were enhanced. Isaac jokingly proposed a business plan to sell fridge magnet souvenirs in Tibet; while I teasingly challenged him for bugee jump at a bypassing site which costed less than three Singapore dollar only! The distance to Kathmandu seemed relatively short in the map; yet we were still on the twisting road and not even close to Kathmandu by noon. Perhaps the downhill view provided not more attractive as that in Tibet, we grumbled into boredom. Finally, around three in the afternoon, we managed to cross the confusing Kathmandu streets congested with horning vehicles and weekend pedestrians and checked into Hotel Vaishali again. I appreciated that the Nepal travel agency made an effort to book an earlier flight to Singapore to us, since we landed in Nepal one day before the stated itinerary due to the foregone Xigar visit previously. However the plan was not realised, so we had practically two full days touring around Thamel. Isaac, yearned for tempura and sushi, lured us into a Japanese restaurant. We had a great meal, at very reasonable price, to celebrate the gain of those memorable experiences from the smooth ending of Tibet tour. We drifted around Thamel aimlessly. While Cheng and I sourced for Tibetan music and postcards for our photo compilation, Isaac ordered a crate of sweet India-imported mangoes.

May 22 (Kathmandu)

This day in Thamel was almost as uneventful as shopping in Orchard Road. We had no intention to venture around Kathmandu since our prior trip more or less presented what we wished to see. We dropped by at our Nepali friend, Saru working hotel shortly. We satisfied Isaac's craze over Japanese cuisine in both lunch and dinner. Even as my mouth was stinted with miso throughout the day, I really enjoyed the cheap but fulfilling set meal in psuedo-Japanese ambiance in each of the different Japanese restaurants. We drifted around Thamel aimlessly. While Cheng and I sourced for Tibetan music and postcards for our photo compilation, Isaac ordered a crate of sweet India-imported mangoes.

May 23 (Kathmandu)

We paid one last visit to Saru in early morning. She introduced her playful niece toddle and her quiet sister, and generously gave us tea leaves as gifts. We departed each other with joys and best wishes before we caught our home-bound flight in the afternoon.